About Tonsillitis and Rheumatic Fever

Rheumatic fever is a disease that can occur following bacterial infection with Group A Streptococcus. Predisposing infections also include strep throat tonsillitis and skin infections, such as impetigo (caused by Streptococcus pyogenes). Overall, rheumatic fever is rare in Australia; however, the rate of rheumatic fever amongst Indigenous Australians is much higher. Rheumatic fever is a serious condition that can lead to long-term complications, such as rheumatic heart disease.

Causes & Pathophysiology

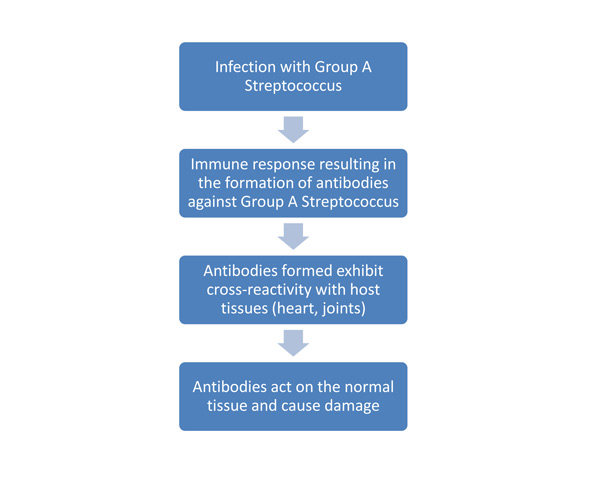

Most commonly, rheumatic fever occurs following tonsillitis, a throat infection with group A Streptococcus. It can also follow skin infections caused by the same organisms. Rheumatic fever is an acute infection with an interesting pathogenesis that can take up to one month to present. It is the result of the immune system producing antibodies to fight off the group A streptococcus infection. Rheumatic fever is considered a type-II hypersensitivity reaction, which means that the antibodies produced by the immune system bind to the antigens on the body’s own tissues and cause a response.

Group A Streptococcus organisms have three predominant factors which help them to establish an infection:

- M proteins: M proteins are found on the surface of the organism and protect it against phagocytosis (breakdown of cells). The M proteins prevent the attachment of complement proteins to the cell. Complement proteins attached to the bacterium are “tagged” for destruction by phagocytes, such as neutrophils and macrophages. This process is called opsonisation. By inhibiting this process, the M protein allows the group A streptococcus to survive longer in the host enabling replication.

- Streptokinase: Streptokinase is an enzyme, which acts by converting an inactive plasma protein, plasminogen, into the active form plasmin. Plasmin breaks down clots of fibrin and other proteins, facilitating the spread of the bacteria from one tissue to another

- Hyaluronidase: Hyaluronidase is an enzyme that breaks down hyaluron, a component of the extracellular matrix in connective tissues. As with streptokinase, this enzyme facilitates the spread of the bacteria through connective tissue

Of these three factors, the one of greatest importance in the pathogenesis of rheumatic fever is the M protein. The M protein on certain strains of group A Streptococcus induce the formation of antibodies which cross-react with certain tissues within the host. The antibodies respond to the “self” antigens presented by the host tissues, which leads to damage of the normal tissues, especially with repeated infections. Most commonly, the tissues that exhibit cross-reactivity are cardiac tissue, joints, nervous tissue and the skin. Because only a very small number of people who have a group A streptococcus infection go on to develop rheumatic fever, it is believed that there may be a genetic predisposition to the condition. In addition, it is very rare for a child under the age of 3 to be affected, suggesting that multiple group A Streptococcus infections are required before developing rheumatic fever. The following flowchart illustrates the basic pathophysiology of rheumatic fever.

Jones Diagnostic Criteria

The Jones criteria are used in the diagnosis of rheumatic fever. The criteria are based on the presenting signs and symptoms. In addition to the presence of a group A Streptococcus infection, a patient needs to fulfil two of the other major criteria, or one major criterion and two minor criteria.

The major criteria for Rheumatic Fever are:

- Carditis: Rheumatic fever can affect all tissues within the heart, including the muscle, valves, linings and coverings. A new murmur may develop, or an existing one may worsen. The mitral valve on the left side of the heart is most commonly affected, followed by the aortic valve

- Joint pain (polyarthritis): the affected joints are very painful and may be treated well with anti-inflammatory medications. The knees, wrists, ankles and elbows are commonly affected. In most cases, the pattern of arthritis is not symmetrical i.e. a joint tends to be affected only on either the left or the right limb, not both.

- Chorea: Chorea is a neurological symptom that is characterised by sudden, seemingly pointless movements. The two most common types associated with rheumatic fever are Sydenham’s chorea and St Vitus’ dance. The person may also behave inappropriately or be upset and have drastic mood and emotional changes.

- Skin Manifestations: Erythema marginatum is a rash that tends to start in the centre of the body and then migrate to the periphery. It generally only affects the parts of the limb closest to the trunk (proximal) and never affects the face. The lesions are generally round with a paler centre and a well-defined red border. It is rare for the rash to accompany rheumatic fever, but is an important manifestation.

- Subcutaneous nodules: These firm nodules form near bones, joints and tendons. Generally, they are not painful. Nodules only occur in about 1% of all cases of rheumatic fever and are associated with carditis.

The minor criteria are:

- Joint pain (arthralgia): it is important to note that if polyarthritis (major symptom) is not present then arthralgia is not considered a minor symptom.

- Fever

- Presence of elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): markers of inflammation that can be detected on a blood test.

- History of rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease

- Prolonged PR interval on an ECG – It is important to note that if carditis (major symptom) is not present then changes in the PR interval are not defined as a minor symptom.

Evidence of a recent infection with group A Streptococcus is the most important diagnostically, as rheumatic fever often follows a group A Streptococcus throat infection. A throat swab may be taken and cultured in the laboratory to determine if there are any organisms in the throat. There is also a series of blood tests performed to provide evidence of antibodies to group A Streptococcus. The level of antibodies may remain raised for several months after the initial infection. These tests are called anti-streptolysin O (ASO) and anti-DNAase B. A recent history of scarlet fever is also evidence of a recent group A Streptococcal infection.

If polyarthritis is present, a small amount of the synovial fluid may be drained to measure the concentration of white blood cells where an increase can indicate the presence of an infection.

Treatment

Treatment for rheumatic fever generally involves antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medications in the attempt to prevent clear the current infection. Initially, a 10-day course of penicillin or erythromycin is recommended to clear the infection and kill the group A Streptococcus. In addition, the polyarthritis associated with rheumatic fever exhibits an excellent response to the prescribed anti-inflammatory, aspirin. Normally, aspirin is recommended for approximately 6-8 weeks in total, with initial doses of 4 times a day. As the treatment progresses the daily dose of anti-inflammatory medication is reduced. Patients with congestive heart failure and moderate-severe enlargement of the heart, glucocorticoids are preferential over aspirin. Patients with chorea may also benefit from anti-psychotic medications, such as haloperidol.

In order to prevent further cases of rheumatic fever, monthly intramuscular injections of benzathine penicillin are recommended. These are commonly given up until approximately 21 years of age. This is necessary as further instances of rheumatic fever may result in rheumatic heart disease, where repeated infection can cause damage to the heart valves. The valves often become thickened and dysfunctional, and may need to be replaced. Infective endocarditis is also more likely to occur with rheumatic heart disease, as the valves are thickened and collections of bacteria, called vegetations, can form on the valve. Infective endocarditis can have a number of complications when parts of the vegetations break off, including stroke and kidney disease. The mitral (bicuspid) valve is most commonly affected in these cases, followed by the aortic valve. In rare, recurrent cases, the tricuspid valve may be affected as well.

Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

Glomerulonephritis is another complication that can occur following either throat or skin infections with group A Streptococcus. It is an inflammatory condition of the filtering blood vessels of the kidney, called the glomeruli. Fewer strains of group A Streptococci are known to cause glomerulonephritis thereby differentiating it from the strains cause only rheumatic fever.

In post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, the antibodies created against the streptococcus combine and cause immune complexes which deposit into the glomeruli. This activates an immune response in the glomeruli, leading to localised inflammation and hence, glomerulonephritis.

The symptoms of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis are:

- Rust-coloured urine

- Blood in the urine

- Decreased amount of urination

- Oedema

- Joint pain and stiffness

If glomerulonephritis were suspected then blood tests performed would be similar to those conducted for rheumatic fever. However, in this condition, a patient may also have high blood pressure. A sample of urine may also be assessed to assist in making the diagnosis.

The main treatment for post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis involves a course of antibiotics (usually penicillin) to kill off the remaining group A Streptococcus. Diuretics may also be prescribed to reduce the amount of fluid in the body and hence the amount of swelling. These may also help to control blood pressure, and in some instances, other blood pressure medications may be used. Unlike rheumatic fever, preventative antibiotic injections are not given to patients with post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, as it is uncommon to have the infection more than once.

If you have concerns about tonsillitis and rheumatic fever make an appointment to see our ear nose and throat specialist.